The susceptibility of smokers to contract COVID-19 has been recognised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and other medical authorities. In Sri Lanka, concerned parties have called for a temporary ban of cigarette sales as a measure to contain the spread of the virus – a commendable move. However, beyond the pandemic, it is important to have appropriate cigarettes taxation measures in place whenever cigarettes are in the market, to reduce consumption, raise government revenue, and reduce the health costs of smoking. Easing the government’s health cost burden from smoking (6% of government revenue in 2015) has become even more crucial amidst the COVID-19 outbreak, where health resources are already stretched thin.

In a previous IPS blog, the case for increasing specific excise tax rates on cigarettes and simplifying Sri Lanka’s existing 5-tier cigarette tax structure was highlighted. Increasing and simplifying excise taxes are prescribed by the WHO Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) and are the most cost-effective tools that governments can employ to reduce smoking rates. However, the tobacco industry strongly opposes raising taxes on cigarettes. Further, Sri Lanka has some misinformed cigarette taxation practices in place, such as taxes differentiated by the length of cigarette and ad hoc cigarette tax changes that are linked to the country’s overall VAT policy. This blog shows the fallacies in these arguments and practices, and highlights the importance of streamlining taxation policies in the country, with the objective of reducing smoking prevalence and reducing smoking related health costs.

Switching to Beedi Consumption

Currently, cigarettes in Sri Lanka are taxed at five different excise duty rates, based on the length of the cigarette (Table 1). As per WHO FCTC recommendations, if Sri Lanka is to simplify its tax structure by taxing all cigarettes at one rate, regardless of length, the tax on shorter cigarettes would have to be increased. Over time, there has been pushback from the tobacco industry to keep taxes low on the cheapest type of cigarette, arguing that raising this tax will incentivise users to switch to beedi consumption. However, the Alcohol and Drug Information Centre’s (ADIC) survey data indicate that beedi consumption has, in fact, declined over time, despite the narrative peddled in media that consumption has increased in response to cigarette tax increases. As a percentage of current smokers, the share of beedi users declined from 11% in 2013 to 5% in 2018. Further, in 2017, only 2.5% of current smokers were found to be substituting cigarettes with beedi, following cigarette price increases; in contrast, 87% reduced cigarette usage and 3% switched to cheaper cigarettes. This evidence contradicts the argument that smokers replace formal cigarettes with illicit cigarettes and beedi.

Taxation versus Pricing of Cigarettes

Prices of cigarettes have continuously increased at a global level, as per the WHO’s calculations. However, such price increases usually consist of a higher net-of-tax price component. Net-of-tax is simply the portion of the price left once the tax is deducted. In Sri Lanka, the price of the most sold cigarette brand (JPGL) increased more than threefold between 2008 and 2018, this increase was due to both the increase of tax per stick (LKR) as well as net-of-tax (Figure 1). This pattern can be observed in other cigarette brands as well. The price of a cigarette borne by the consumer consists of production cost, profit, and tax. A marked feature here is that a high share of the net-of-tax price is absorbed as a profit margin by the producer, which eventually results in pushing prices up by more than the tax increase, while stagnating the government tax revenue.

As such, although tax increases – to which the industry is resistant – usually push prices up, the beneficiary tends to be the cigarette industry, rather than the government, gaining a higher markup than tax revenue, respectively.

Value Added Taxes (VAT) on Cigarettes

A problematic feature of Sri Lanka’s cigarette taxation policy is that, over time, tax policy has fluctuated according to changes in the country’s overall VAT rate. The VAT is applied on several goods in Sri Lanka, and is a fixed rate that is common to all goods that fall into the VAT net. Cigarettes have both excise duties and VAT applied on them. However, when the overall VAT rate in the country fluctuates based on external factors unrelated to cigarettes, excise taxes are adjusted to reflect this change. This is not in line with best practices; excise rates should be raised to adjust for changes in inflation and income, and not according to changes in VAT. This is because cigarettes might still be affordable for consumers, if the price is not raised to reflect a rise in inflation or income.

For instance, in 2014, cigarettes were exempted from VAT and so excise rates on cigarettes were raised to adjust for the shortfall in revenue. More recently, in 2019, the VAT rate was reduced from 15% to 8%, so excise rates on cigarettes were raised for the same reason. As such, there is a tendency for movements in the excise tax to be determined by changes in the VAT rate, rather than be adjusted in line with inflation and income. It is important that cigarette tax policy focuses on raising excise taxes, independent to VAT rate movements.

Conclusion

The blog flags and debunks three arguments against the WHO recommendations to raise excise taxes on cigarettes and establishes that (1) although there is a negligible trend in switching to lower-priced cigarettes, the common response to price rising is the reduction of cigarette consumption, not replacing the tobacco consumption with illicit cigarettes and beedi, (2) the producer has benefited more from cigarette tax/price increases than the government in terms of revenue per stick, and (3) the effectiveness of cigarette taxation vastly depends on the type of tax imposed. As such, separating ad-valorem taxes from excise tax on cigarettes and following-up the WHO recommendation (specific excise taxation with inflation and income adjustment) is the most effective way of curbing cigarette consumption as well as increasing government tax revenue.

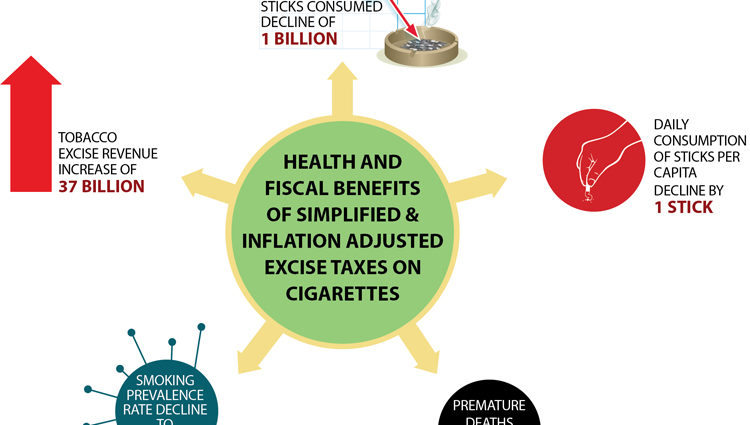

A forthcoming IPS study estimates through a tax modelling exercise, that if (1) excise taxes on cigarettes were raised to adjust for inflation such that they become less affordable, and if (2) the existing tier structure was incrementally collapsed into a uniform tax rate over a four year period, government revenue from tobacco will increase by LKR 37 billion, cigarette consumption will decline by one billion sticks, smoking prevalence (of +15 years) will decline to 12.5%, with the number of premature deaths from tobacco use that can be avoided in the future amounting to 141,391. These are significant outcomes for Sri Lanka’s health and fiscal space, and can be implemented at no cost to the government. As such, it is suggested to increase tobacco taxes in this manner, to increase tax revenue and reduce health costs incurred by the government, regardless of industry pressure against the implementation of such policies.